Brief History of Timbuctoo

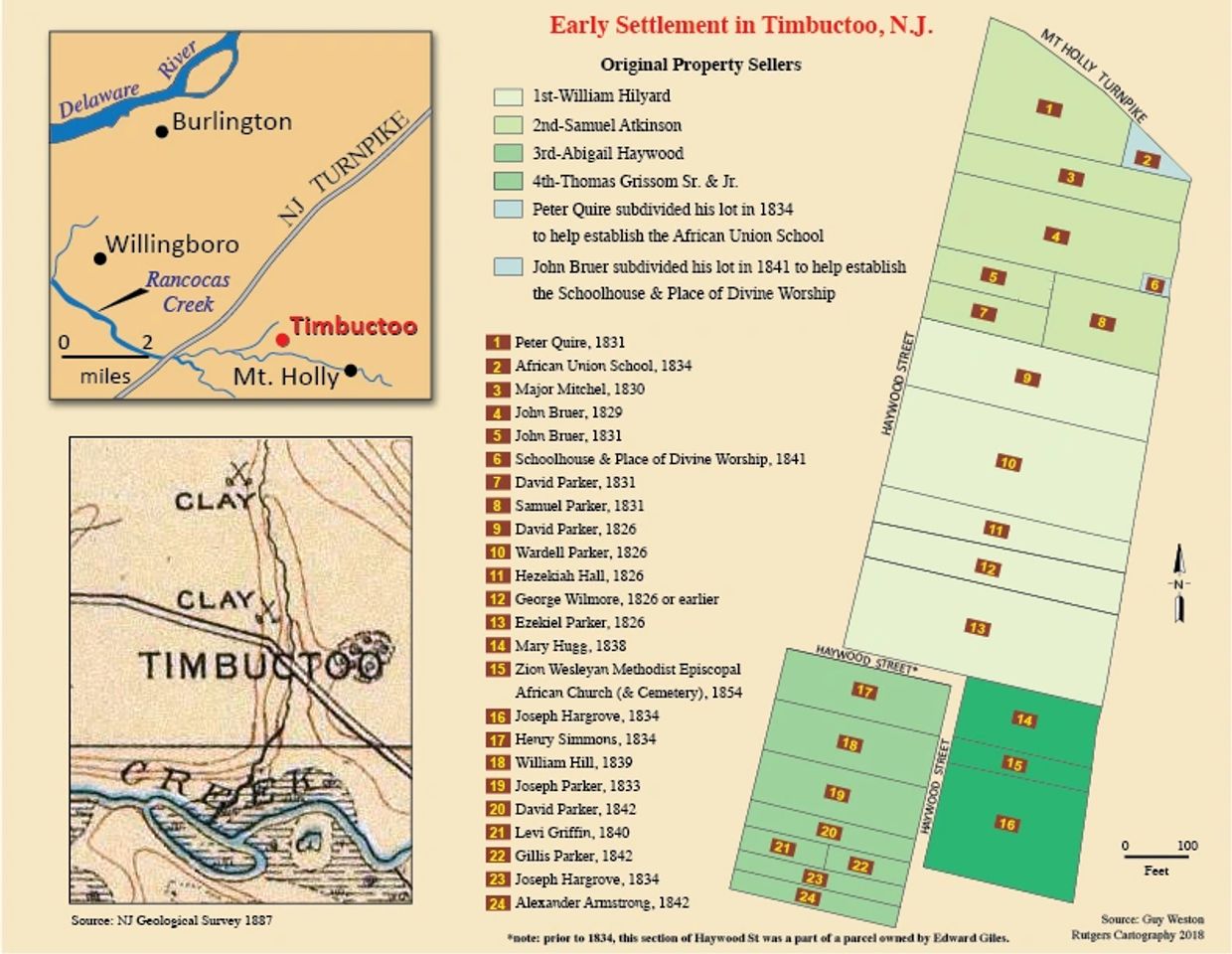

Settlement in what would later be known as Timbuctoo began in September of 1826, when David Parker, Wardell Parker, Ezekiel Parker, and Hezekiah Hall purchased parcels of land from a Quaker businessman named William Hilyard. The four buyers were already residents of Burlington County at the time, but they all had previously escaped enslavement in Maryland. The fifth recorded purchase was by John Bruer in 1829. The seller in that case was a Quaker farmer by the name of Samuel Atkinson. Over the next two decades, about two dozen land transactions would occur, including homesteads, as well as a school, a church, and a “schoolhouse and place of divine worship,” which appears to have been used for schooling as well as worship services.

Deeds from early to mid-nineteenth century institutions provide interesting details about the community and the state of affairs for these fledgling early settlers. For example, the deed for a parcel to establish the African Union School says:

“Whereas, in the Settlement of Tombuctoo…and in the vicinity thereof, there are many People of Colour (so called), who seem sensible of the advantages of a suitable school education and are destitute for a house for that purpose. And the said Peter Quire, and Maria, his wife in consideration of the premises, and the affection they bear to the People of Colour, and the desire they have, to promote their true and best interests, are minded to settle, give, grant and convey…said premises to the uses and intents hereinafter pointed out and described.”

This deed also stipulated that future board members had to be “People of Color” who lived within 10 miles of the premises. Considering that deeds are recorded in the office of the Burlington County Clerk, and that recording legal documents in that era meant an official had to hand write a second copy for the official record, the restrictive language about board membership could not be unknown to county officials. This arrangement runs counter to what many of us learn about efforts to teach Black people to read in the early decades of the Nineteenth Century. Was this a bold act of defiance by Timbuctoo leaders that could have faced retribution, or was the county clerk a known ally?

Similarly, the deed for the Zion Wesleyan Methodist Episcopal African Church and cemetery, dated 1854, gives some insight to this church’s mission, organizational affiliation, and rules for determining who could be buried in the church’s cemetery. In this case, we learn that Zion Wesleyan was an AME Zion church, because the deed says:

“…the said lot of land hereditaments and premises hereby granted and released or mentioned or intended so to be with the appurtenances unto the said Trustees of Zion Wesleyan Methodist Episcopal African Church and their successors to the only proper use and benefit and behoof of the said Trustees and their successors to be used as a place of religious worship according to the form of government and discipline of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in America, and as a place for the burial of the dead of such as are in connection with said church or the descendants thereof, (and such others as the majority of the Trustees for the time being may permit) forever.”

In his History of the AME Zion Church, David Henry Bradley Sr., describes the early years of this denomination as having an "antagonism to slavery," He also notes that renowned abolitionists Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, and Frederick Douglass, were members of the AME Zion Church. Bradley goes on to explain the AME Zion church’s position of leaving “no stone unturned” in efforts on behalf Black people remaining in bondage, “that churches were borne out of a grave necessity to bring…(a) new interpretation of Christ into the hearts of men who merely wondered about God’s interest in men of low estate,” and that “Zion ministers were expected to take an active part in this struggle for freedom.” The AME Zion church was known as the freedom church as a result of these activities. It comes as no surprise that such a church was established in Timbuctoo.

Timbuctoo was never particularly large. At its peak in the nineteenth century, Timbuctoo reportedly had about 125 residents. As late as 1966, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported approximately 100 residents. Today Timbuctoo has approximately 19 households spread over fifty acres. Current zoning regulations require at least one acre for new home construction.

Much more can be learned about Timbuctoo by visiting our Informational Resources tab, which includes journal and magazine articles, and

PowerPoint presentations, some of which are on video. In addition, newspaper articles cover recent preservation and educational efforts, and a link to our curriculum page has resources for teaching about Timbuctoo and antebellum free Black communities for middle school and high school students.

There are also historic newspaper articles from as early as 1851 available. Transcription of articles is ongoing and new ones are added periodically.

See Five Fast Facts About Timbuctoo, below for a concise summary some major milestones of Timbuctoo history.

Back to Home Page